Brigadier General Albie Götze: the only surviving pilot in South Africa to have been involved in the D-Day landings

Some people are old at 18, and some are young

at 90… time is a concept that humans created

– Yoko Ono

THEN AND NOW Albie is almost as on the ball as he was back in the day of 1944.

Speaking to 93-year-old Onrus resident Albie Götze, one can well believe the above quote might be true. When I arrive at his lodgings he is poring over an article on splicing defective DNA from the helix and replacing it with new strands.

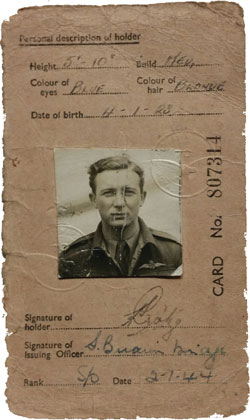

SKRIK VIR NIKS Albie was summarily dispatched in a glider and informed that ”if you can land this thing, you’re in”. He was just 17 at the time.

From a somewhat inauspicious background, Albie Götze literally took his life to new heights as a fighter pilot in WWII. If offered the chance to fly a Spitfire or a Typhoon, or anything really, or parachute out of a plane, chances are Albie would still say yes.

Born on a farm near Prieska to a German father and Afrikaans mother, things went somewhat haywire when Albie was in Standard four and his father, through no fault of his own, went bankrupt. At the same time, his mother, Joey, was ill with rheumatic fever and the family was advised to move to Cape Town for the air. Attending Hoërskool Jan van Riebeeck in Kloof Street, bright spark Albie was put up a standard, thus finishing matric at a young 17 in 1939, just as WWII was breaking out.

At first, Albie worked at Maskew Miller, “changing pen nibs”, as he puts it. He was musically gifted — his mother taught him to play the piano when he was four, but the precocious Albie said he could prefer the violin, which he learnt remarkably quickly. He studied music in Cape Town and formed a trio with Maria Venter and Paul Fouche, playing live on radio. He also played in a brass band, singing and playing the violin at the Cape Town Eisteddfod.

The family was desperately poor, and it was left to Albie to take care of his mother, take himself to school, feed and clothe them, and attend his music lessons, and he loved every minute of it! “But eventually my mother moved back to Prieska and I went to Johannesburg for my public service exams. I had housing in the railway lodging in Langlaagte – it was too terrible,” he laughs.

I was a prefect at the hostel, but a few friends and I were turfed out over some high jinks and a water fight. “We were poor whites, after all!” Forced then to move in to a flat above a bar, the friends quickly took to thrashing the locals at snooker. “We virtually made our living that way,” he jokes.

“Then we joined the Ossewabrandwag, running through the hills with brooms for rifles. We were just kids. But then I got the opportunity to enlist with the South African Air Force Association (SAAFA) – even though my father was German, he was vehemently anti-Hitler and the SS. I was given a glider on a mountain top and told, “If you can land this, you’re in.” Thereafter, he and a close friend, Henri Kuiper, were duly sent off to flying school at Lyttelton in 1942 and qualified for wingsin 1943.

HAVE WHEELS, WILL RIDE Albie is well known around Onrus Village in his ‘red Ferrari’ – no

way was Albie going to be confined to his flat.

Albie was then dispatched to the Middle East, Egypt and Palestine, and to England with the 127 Spitfire Squadron Royal Air Force (RAF). He flew patrols and bomber escorts into Europe and was also involved in shooting down V- 1 flying bombs, and provided flying cover for D-Day landings.

“Skrik vir niks”, Albie flew Hawker Typhoon ground attack aircraft at very low levels, which was extremely dangerous, to say the very least. He suffered many hits, but the enemy suffered more. “You should see the other guy!” he laughs. On one occasion his Typhoon took a hit in the fuselage, but, miraculously, it didn’t explode, and Albie had to come in to land at a 40 degree incline.

In 1944 he was responsible for introducing and implementing the South African air defence system as Chief Air Defence Operations Officer.

After being demobbed in 1946, Albie was asked whether he wanted to join the now SADF permanently. Need I even say that he agreed? Training in simulation in Spitfires, as well as having to become an expert navigator, Albie then participated in the Berlin Airlift, flying supplies in to the besieged city, and in 1951 he completed a tour with the South African Air Force no. 2 squadron to Korea, where he flew P-51 Mustangs.

OPERATION MARKET GARDEN Despite the best of intentions and planning, the failure of

Market Garden to form a foothold over the Rhine ended Allied expectations of finishing the war by Christmas 1944.

Besides his love affair with the air, Albie also acted as secretary to then President Nicolaas Diederichs for three years and managed to find time to get married – twice. His first wife, Betsy, to whom he was married for 44 years, died of cancer in 1993. They had one son, Hugo, who is a pharmacist in Hermanus and pops in regularly to take his dad out in his “red Ferrari” – a mobility scooter that ensures Albie “gets out and about more than enough”, jokes Hugo.

Since moving here Albie has reconnected with fellow fighter pilot Henri Kuiper, who also lives in Hermanus. “Since reconnecting we have enjoyed a close friendship and share memories of air combat, service and aeronautical knowledge,” says Albie. Nowadays he is also writing a book. “My book is being completed; however, it will be for my family only.” Albie has three grandchildren and seven great grandchildren.